|

|

Anglican Traditions

Many of us come to church each week, take part in the worship and fellowship, and become part of the

church community. However, many times we realize that we don’t know why

certain things are the way they are in the church. For example, some

might wonder about some part of the liturgy. Others might be interested in

the significance of the vestments that the priests wear. A few might like

to better understand the structure of the Eucharist.

Recently, in response to many questions posed to the

clergy, an excellent series of questions and answers, relative to our

services and other Anglican customs and traditions, was published recently

in a sister church's bulletin. By request, these are being repeated on this parish

website.

In addition, many other items of a similar nature

have appeared in other publications over the years. These are

included, via the underlined links shown below, and also in the menu bar at the

top of every page.

We hope you enjoy reading these valuable and informative pieces.

Our Anglican Church

- nave, narthex, tabernacle /aumbry

The Liturgy:

Easter:

Our

Anglican Church

|

NAVE |

Question:

Answer: |

Where is the nave? Where does the word come from?

The nave is the part of the church in which the congregation sits. It

generally has an aisle on each side and an aisle up the center. It

comes from the Latin word 'navis', meaning a ship. So the church is

sometimes referred to as a ship, where we can retreat for refuge as we

journey through the seas and storms of life. Great imagery, isn't it?

|

|

NARTHEX |

Question:

Answer: |

What is the origin of the word narthex?

Narthex comes from the Greek word narthex, meaning enclosure. Narthex

is the antechamber of the nave, from which it is separated by columns,

rails, or a wall. In the early church, the catechumens, which were the

candidates for baptism, and penitents sat in the narthex.

|

|

TABERNACLE/ AUMBRY |

Question:

Answer: |

What is the difference between the tabernacle and an aumbry?

On or near an altar there may be a receptacle. If this is on the altar

it is known as a tabernacle. If set into the wall it is known as an

aumbry. An aumbry is usually a small locked safe

that contains the blessed sacrament - the consecrated bread from the Eucharist.

It is reserved so that Holy Communion can be taken to the sick or shut-ins

at short notice. The locked safe also contains holy oil that is used

at baptisms and for the Sacrament of Holy Unction and the Laying On of

Hands.

|

↑

Back to page top

Definitions

|

LITURGY |

Question:

Answer: |

When I was young I never heard the word Liturgy. It was always the

Eucharist of Holy Communion. Where did the word Liturgy come from?

One of the names most frequently used nowadays for the Eucharist or Holy

Communion service is the "Liturgy". This word derives from two Greek

words which may be translated "the people's work". This is a helpful

definition of worship as applied to the Christian Church. We, the

people of God, have a job to do. We are sent - sent out into the world

to be the salt of the earth, the leaven in the lump. Part of our work

is worship; and the principal act of worship is the holy Eucharist, the

Lord's Supper, the Liturgy. So our work becomes our delight!

|

|

APOSTLES/ DISCIPLES |

Question: Answer: |

What is the difference between an apostle and a disciple?

Good question! Depending on the theologian, the answer may vary.

However, this is what I believe.

An apostle is one of the twelve disciples chosen directly by Christ and sent

to preach the gospel to all the world. Apostle comes from the Greek work

signifying ‘sent’. Jesus sent the twelve with the commission to teach and

to act in His name and with His authority.

Paul maintained that he was an apostle too, on a par with the twelve, by

direct appointment by the risen Christ. So the designation apostle is

reserved for the Twelve and Paul. These men were unique.

A disciple is a believer in the thought and the teaching of Jesus. In

short, they are followers. You and I would be considered disciples of

Christ.

In conclusion, every apostle was a disciple, but not every disciple is an

apostle.

|

|

ALLELUIA/ AMEN |

Question: Answer: |

What is the meaning of the words

Alleluia and Amen?

Alleluia comes from the Hebrew word

meaning ‘praise the Lord’. So, it is a liturgical expression of praise. It

occurs in the bible (e.g. in pss. 111-117) and it was taken early into the

liturgy of the Church. In the Western Churches it is omitted from the

Liturgy during Lent. As an expression of joy, it is used frequently during

the period of Eastertide.

Did you know that in the Eastern Churches, Alleluias occur with special

frequency during the Lenten services?

Amen is a Hebrew word meaning ‘verily’ or ‘truly’. It is used at the end of

prayers and creeds as an expression of our agreement or assent. Did you

know that Amen is the name given to our Lord in the Book of Revelation?

(3:14)

|

|

PAUL and the GOSPELS |

Question

Answer:

|

What is the time frame when Paul was writing his letters? How do they

relate to the gospels: Paul probably wrote his letters in the period

between 51 and 63 A.D. (He was martyred about 64 A.D.) They were

written for the instruction and encouragement of new Christian Churches.

The gospels came later, when the Church realized that the second coming of

Christ wasn't happening as soon as expected. Mark's was the first to

be written, around 70 A.D. The Church gave the gospels the most

honored place as witnessing to Jesus' life and teachings, His death and

resurrection, while treasuring Paul's letters as an inspired exposition of

the Christian faith. |

↑ Back to top

Liturgy of God's Holy Word

(The basis of our Liturgy in the practice

of the Early Church)

|

The Introit Psalm |

During the period A.D. 422-432, the custom developed of beginning the

Eucharistic Liturgy with a Psalm (the Psalter is the hymn book of Judaism

with which our Lord was familiar).

|

|

The Lord's Prayer |

and the Collect for Purity are all that remain from the priest's

preliminary preparation with his assistants appointed to be said before the

Mass in the Sarum Missal used in Salisbury, England, in 1237.

|

|

The Decalogue |

(Exodus 20:1-17) or Christ's Summary of the Law (Matthew 22:37-40)

were added in place of the 9-fold Kyrie in 1552 and 1789 respectively.

|

|

The Kyrie |

as a response can be traced back to the fourth century in the Eastern

Orthodox Liturgies.

|

|

The Gloria in Excelsis |

In the Orthodox Liturgies of St. Basil and St. John Chrysostom, a familiar

and popular hymn was sung at the beginning of the rite (except in Advent and

Lent). Since the 4th century, the most popular hymn has been the

Gloria in Excelsis.

|

|

The Salutation |

This ancient greeting initiates the major portions of the Eucharist - The

Liturgy of the Word (Bible Readings) and the Liturgy of the Altar Table.

|

|

The Collect of the Day |

Beginning in the 5th century, the Egyptian Prayer Book of Serapion

introduced a prayer related to the lessons which follow.

|

|

The Three Lessons |

The early Christian Church read the Jewish scriptures (Old Testament) and

added Christian writings which, by the year A.D. 382, had been compiled into

the New Testament by the Church. Soon the tradition was fixed of

reading 3 Lessons (Old Testament, Acts or Epistle, and Gospel), some of

those lessons being 2 or 3 chapters in length. In the Middle Ages, the

Roman Rite reduced the readings to 2 short lessons.

|

|

The Psalms |

The use of a Psalm after the Old Testament reading can be documented as

early as A.D. 350 and represents the oldest use of Hymnology (psalms) in the

Liturgy. As early as the "Martyrdom of Matthew" (3rd Century),

Alleluias were sung in anticipation of the Gospel reading. The Roman

Rite dropped the Alleluias in Lent.

|

|

Sequence Hymn |

The use of a Sequence Hymn appears in the 9th century.

|

|

The Reading of the Gospel |

The reading of the Gospel has attracted special ceremonies since the 4th

century. The Gospel Book came to be carried into Church accompanied by

incense and candles, and placed on the Altar until the Gospel procession.

The reading of the Gospel and the Book itself symbolized the presence of

Christ in the Liturgy of the Word, just as the Eucharistic Prayer and the

elements of bread and wine are the focal points of Christ's presence in the

Liturgy of the Table.

|

|

The Nicene Creed |

In the first centuries, the Eucharistic Prayer of Consecration was

understood as being the Creed in which the people heard their faith

proclaimed over the bread and wine and gave their assent in acclamations and

"Amen". The Nicene Creed originated in the Eastern Churches as a

baptismal profession of faith with a structure modeled on Matthew 28:19 and

an emphasis on oneness that reflects Ephesians 4:4. Amplified by the

Council of Nicaea (A.D.325), the Nicene Creed was introduced into the

Western Church at the council of Toledo in Spain in A.D. 589.

(see also the special section on the Nicene and Apostles' Creeds.)

|

|

The Preparation of the Table and the Presentation of Offerings |

The action of worship now moves from the pulpit (lessons and sermon), the

piece of furniture and symbolizes Christ's presence in the world, to the

Altar, the Table which is the centre of His presence in the Sacrament.

Soon after Constantine legalized Christianity (A.D. 313) it became customary

for a psalm or hymn to be sung during the presentation of the gifts of

bread, wine and money. "Let all mortal flesh keep silence" was the

most popular hymn in the Eastern Church. The new American Prayer Book

of 1979 lists places where incense is used. In the "Commentary"

thereon, the following explanation is offered:

"In the ancient Jewish Temple an incense offering was burned by the priest

every morning and evening (Exodus 30:1-10; Luke 1:8-23). Incense was a

worthy, expensive gift offered to God (Matthew 2:11; Philippians 4:18;

Revelation 18:13), and signified the ascent of the prayers of people to God

(Psalm 151:2; Revelation 5:8 and 8:3-4). The smoke of incense is seen

in both the Old and New Testaments as the manifestation of God's glory (1

Kings 8:10-11; Isaiah 6:6-8 and Revelation 15:8)."

|

|

The Intercessions |

By the end of the 4th century in the Eastern Church, these prayers had

become a Litany with biddings by the Deacon to which the people responded "Kyrie

eleison". In the new Liturgies, the Intercession is restored to its

earlier position before the Offertory.

|

|

The General Confession |

A general confession of sin by the whole congregation was an innovation of

the 16th century. Earlier, the Lord's Prayer, which concluded the

Prayer of Consecration and contained the phrase "forgive us as we forgive"

sufficed. No absolution was included for one of the benefits of

Communion was understood to be the forgiveness of sins.

|

|

Thanksgiving over the Bread and Wine (the Prayer of Consecration) |

For the first several centuries the text of this prayer was not fixed.

By the 4th century in the East, the Eucharistic Prayer had developed a

formalized Trinitarian pattern (like the Creed); God the Father was blessed

for Creation and Redemption, the Redemptive work of Christ was recalled and

the benefits of the Spirit were invoked.

|

|

The Lord's Prayer |

By A.D. 400 the Lord's Prayer was used as a devotion preparatory to

receiving Holy Communion, e.g., "give us this day our daily bread". In

590 Gregory the Great placed it immediately after the Amen of the

Eucharistic Prayer. During the 16th century it came to be said after

Holy Communion, but is now universally being restored to its original

position in the Liturgy.

|

|

Prayer of Humble Access |

This was added in the 16th century and is not included in most new

Liturgies.

|

|

Holy Communion |

The traditional posture for Christians receiving Communion is standing, a

tradition the Eastern Churches have always maintained. In the late

Middle Ages, the custom developed in the West of kneeling to receive

Communion. The Words "The Body of Christ" and "The Blood of Christ"

were sentences of administration from the earliest times which constituted a

profession of faith to which the communicant answered "Amen".

|

|

The Post Communion Prayer |

Until the 4th century the rite ended with Communion. Gradually a

dismissal was added which included a formal prayer and an act of sending

people on their way to go about the Lord's business, acting out in the world

what they had just celebrated.

|

|

The Blessing |

There is no evidence of a blessing at the end of the Eucharist in the Early

Church. By the Middle Ages the Bishop said a blessing over the people

as he walked through the Church, and in the 16th century this blessing came

to be said in many places at the Altar. Many new rites omit the

blessing, considering it to be superfluous to the act of Communion.

|

↑ Back to top

Today's

Eucharist

|

PROPERS |

Question:

Answer: |

What are the Propers and what is the origin of the word?

Propers come from the word Proper. Together the Collect, the Old

Testament Reading, the Psalm, the Epistle, the Gospel and the Preface are

called the Propers. They are fitting or Proper for our 3-year

calendar.

|

|

COLLECTS |

Question:

Answer: |

What are the Collects? Who prepares them? Do they change from

year to year?

The Collect (from the word collect, meaning to gather) is a prayer where we

ask God, the Holy Spirit, to collect (to gather) our thoughts for the

readings that follow. The Collects follow a 1-year cycle for all

Sundays of the Liturgical year. There are special Collects for

festivals, saints' days and holy days. The Collects are prepared by

liturgical experts to follow the Church calendar. |

|

GOSPEL |

Question:

Answer: |

How is the Gospel reading different from the rest of the New Testament?

The first 4 books of the New Testament, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, are

the accounts of the life, death, resurrection and teachings of Jesus.

They are called Gospels from the old English word godspell,

meaning "good news". At every Eucharist the reading from one of the

Gospels is the climax of the readings and is given special honour. |

|

BELLS |

Question:

Answer: |

What is the significance of the bells during the Eucharist?

When the Sanctus bells are used, they are rung 3 times at the words Holy,

Holy, Holy. The bells announce that the most sacred part of the

service (the Prayer of Consecration) is starting. Their use is

ancient. It is said that originally the Church bell was used so that

the peasants in the fields (who could not attend the service) would know

when the most sacred parts of the service were taking place. They

could then join with the congregation by offering personal devotions.

The Sanctus bells are rung again, after the consecration of the bread,

announcing that Christ is present in the bread. Again, they are rung

after the consecration of the wine, announcing that Christ is now present in

the wine. |

|

OFFERTORY |

Question:

Answer: |

What is the Offertory?

The Offertory is the part of the Eucharist in which the offering takes

place. It includes the collection of money (alms), its presentation to

God, the placing of the elements, bread and wine upon the altar, and

whatever is said or sung at that time. These signify the presentation

of the worshippers themselves. The collection of money is only one

part of the Offertory. |

↑ Back to top

The Vestments

|

Question:

Answer:

|

Why are vestments worn by the Priest during worship?

Also, why do choir members and servers have to wear robes in some churches?

There are several answers to these questions.

- Vestments and robes add to the dignity of the worship offered to God.

- They save the worshipers from being distracted by the passion fashions

of street dress.

- They emphasize the official character of those who lead worship,

thereby lessening the effect of the individual personalities.

- In addition to these above, vestments have a symbolic value - they

represent something in our faith, which is further addressed below.

|

Question:

Answer: |

What is the significance of the vestments worn by a Priest during worship?

In many churches you will see Eucharistic vestments worn

by the celebrant at the Eucharist. Every one of these vestments has a

meaning which is related to Christ’s crucifixion.

-

The Alb is a white linen garment

which covers the entire body. The alb represents the purple robe put on

Christ in mockery, but is white to symbolize His innocence. It reminds us

of the purity and innocence which is required to approach God. Alb comes

from a Latin word which means white.

-

The Stole and the Girdle (or

Cincture). The Stole is a long scarf which is crossed over the chest and

held in place by the Girdle which looks very much like a white rope. The

Stole and Girdle symbolize the ropes used to tie Christ to the pillar when

he was scourged. Furthermore, the stole for a priest is like a badge for

a policeman, it tells us that the person who wears it has a special job to

do. The Priest’s work is to be God’s representative to us. And just as

important, the Priest is our representative before God.

-

The Chasuble is a large oval

garment made of linen or silk. It is sleeveless and has a hole in the

center to slip over the Priest’s head. It falls straight from the

shoulders. The Chasuble reminds us of the seamless robe put on Christ

before He was lead away to the cross. It is a sign of Christ’s love for

us. It also represents love in reference to St. Paul’s injunction, “above

all things put on love” (Col 3:14).

|

↑ Back to top

Liturgical Colors

The earliest definite knowledge of the use of specific

color in the service of the Church is Clement of Alexandria' recommendation of

white as suitable to all Christians. The Canons of Hippolytus assign white

to the clergy as becoming their office. The medieval development of color

symbolism may be examined in the Rationale Divinorum Officiorum of Durandus.

This 13th Century prelate explains the meaning of all colors but, interestingly

enough, knows of no such thing as either a standard Use or a standard meaning.

The ancient Use of liturgical colors was very simple:

the best vestments, second best, ordinary and, in some places, black. The

Eastern Orthodox Church still adheres to this practice. Insofar as "the

best" is concerned, it is still required by the Dominican Order's Rule to be

worn on the highest feasts irrespective of its color.

In the middle ages each Cathedral had its own Use, and

although Use was by no means binding on the Diocese involved, it was inevitable

that some sequences should become popular and that, ultimately, certain

Cathedral Uses should grow wider even than diocesan in their influence. It

must be noted, however, that on an Ascension Day in the 16th Century, one could

have seen "the best" vestments in Salisbury, white in Westminster, blue in the

College of St. Bernard, yellow in Prague, red in Utrecht, and green in Soissons.

The Use of Salisbury Cathedral (Old Sarum) has always had

wide popularity; therefore it should be noted that the ancient Westminster Use,

which was predominately white, red and black, has always had considerable

appeal.

The Best: Christmas, Epiphany, Easter, Ascension,

Whitsunday, Trinity, Dedication, Patronal Festival, All Saints', Thanksgiving.

2nd Best: Weekday in Epiphanytide, Trinitytide (if red not used).

The color sequence of the Roman Catholic Church

(generally adopted by the Anglican Church) is now very largely that common to

the Court of Rome in the 16th Century. It is often referred to as the

Western Use. It is as listed below:

White:

Christmas and days of Octave ending with Circumcision (Jan. 1), Epiphany and

Octave, Easter Even through the 5th Sunday after Easter, Ascension Eve through

the Vigil of Pentecost, Trinity Sunday, Transfiguration, Christ the King, All

Saints. Depicts joyfulness.

Red:

Pentecost and Octave, Apostles and Evangelists

(except John, whose feast is a white one). Red has become increasingly

used during Holy Week. Depicts the colour of blood, and used to

commemorate all martyrs and for the Holy Spirit.

Blue:

Advent

Purple (Violet):

Lent. Depicts penitence

Green:

The Sundays (and Ferias) after the Octave of

Epiphany through to the Eve of Septuagesima or, more often now. to Ash

Wednesday, the Sundays after Pentecost (or after Trinity) through to Advent.

Depicts patient growth.

Black: Good

Friday, All Souls', Requiems

Rose:

The 3rd Sunday in Advent, the 4th Sunday in Lent.

↑ Back to top

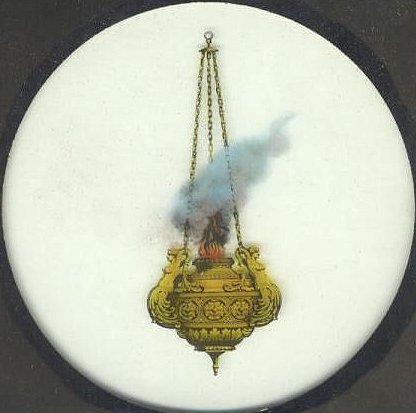

Significance of Incense

|

Question: |

Christmas is coming and we usually

use incense in the service. Can you talk a little about incense?

|

|

Answer: |

Incense signifies prayer and

sacrifice and is also a sign of honor and respect. The Bible contains many

references to incense in worship, perhaps the most notable being in St.

Luke, chapter 1, verses 8 to 12. Also the psalmist writes, “let my prayer

be set forth as the incense, and let the lifting up of my hands be an

evening sacrifice” (Psalm 141:2). During the days of persecution in the

early church, attempts were often made to force Christians to burn incense

in front of a statue of the Roman Emperor. To do so, of course, was to turn

one’s back on Christ. It is not surprising, therefore, that it eventually

became common practice for Christians to use incense in their worship to

acknowledge Christ as their divine Ruler. The server who looks after the

incense is called the thurifer; the vessel he carries containing burning

charcoal, is the thurible. He has the incense in a container called a boat,

which may be carried by a ‘boat boy’, usually a small server.

Incense signifies prayer and

sacrifice and is also a sign of honor and respect. The Bible contains many

references to incense in worship, perhaps the most notable being in St.

Luke, chapter 1, verses 8 to 12. Also the psalmist writes, “let my prayer

be set forth as the incense, and let the lifting up of my hands be an

evening sacrifice” (Psalm 141:2). During the days of persecution in the

early church, attempts were often made to force Christians to burn incense

in front of a statue of the Roman Emperor. To do so, of course, was to turn

one’s back on Christ. It is not surprising, therefore, that it eventually

became common practice for Christians to use incense in their worship to

acknowledge Christ as their divine Ruler. The server who looks after the

incense is called the thurifer; the vessel he carries containing burning

charcoal, is the thurible. He has the incense in a container called a boat,

which may be carried by a ‘boat boy’, usually a small server.

During the Eucharist incense may

appear at any or all of the following times: at the head of the procession

from the sacristy to the altar; at the head of major processions both inside

and outside the church; at the altar, which may be censed at the beginning

of the service; during the Gospel; at the offertory; and at the elevations

of the host and chalice. If the congregation is censed at the offertory,

the people bow to the thurifer before and after being censed; we are all

involved in the sacrifice and we are a ‘holy people’.

|

↑ Back to top

Use of

Candles

| Question: |

Why do we use candles during the liturgy?

|

| Answer: |

Our Lord is the light of the world

(John 8:12). At baptism we are made one with him; we join his family and

are ourselves ‘to shine as lights in the world to the glory of God.’ The

symbol of a lighted candle, then, has an obvious meaning; this is why we

present one to the newly baptized, one that has been lit from the Paschal

Candle that stands near the font.

Our Lord is the light of the world

(John 8:12). At baptism we are made one with him; we join his family and

are ourselves ‘to shine as lights in the world to the glory of God.’ The

symbol of a lighted candle, then, has an obvious meaning; this is why we

present one to the newly baptized, one that has been lit from the Paschal

Candle that stands near the font.

On Easter Eve a large candle– the

Paschal Candle– is carried into the darkened church, with the joyful

announcement, ‘the light of Christ!’ This candle burns during services

throughout Eastertide, after which it is placed near the font. One thing we

learn from this is that we are enabled to shine as lights in the world only

in and through the light of Christ himself.

Candles are also found on altars to

remind us of the presence of Christ; they are usually in an even number (2,

4 or 6); this may serve to remind us that Jesus is both true God and true

man.

The Eucharist is made more dignified

and solemn by the carrying of candles by servers called acolytes or

torch-bearers. Candles have been used at the holy communion from the very

earliest times.

|

↑ Back to top

The

Nicene and Apostles' Creeds

NICENE

CREED |

Question:

Answer: |

Where does the Nicene Creed come from?

The Nicene Creed is the great Creed of the Church, so called from a town

named Nicaea, in Asia Minor, where it was drawn up in 325. It was drawn up

to defend the orthodox faith against Arianism. This heresy denied the full

divinity of Christ, and was named after its author Arius. Arius held the

view that the Son of God was not eternal but created by the Father from

nothing as an instrument for the Creation of the world. He was therefore

not God by nature, but a creature susceptible of change, even though he

differed from other creatures in being the one direct creation of God.

|

|

APOSTLES' CREED |

Question:

Answer: |

Where does the Apostles’ Creed come from?

The Apostles’ Creed comes from the summary of the

doctrine taught by the Apostles.

It is the oldest form of creed in existence in the Church.

|

|

THE DIFFERENCE |

Question:

Answer: |

What is the difference between the Nicene Creed and the

Apostles’ Creed?

The Apostles’ Creed is different from the Nicene

Creed.

The Apostles’ Creed was not written by the Apostles but it is a summary of

the doctrine taught by the Apostles. It is a statement of faith used in the

Western Church. It has three sections: One dealing with God the Father;

the second dealing with Jesus Christ; and the third dealing with the Holy

Spirit. It is a much shorter form of our belief and was originally used in

the early Church for the preparation of candidates for baptism. By the 7th

and 9th centuries it was used regularly in the daily offices.

The Nicene Creed, as stated in the above answer, was written and used as a

standard of orthodoxy. It is a much longer statement of our faith because

it was written to clarify and to respond to heresies that were creeping into

Church doctrine. The practice of reciting the Nicene Creed started in the

Eastern Church in the 5th century. It was not adopted in the West until the

early 11th century.

Therefore, the Apostles’ Creed is a summary of important points in Christian

doctrine. The Nicene Creed clarifies and elaborates our Christian beliefs.

|

|

USING ONE INSTEAD OF THE OTHER |

Question:

Answer: |

Why do we use the Nicene Creed instead of the Apostles’ Creed?

It was in the Eucharistic Prayer, rather than in

the Creed, that the ancient church gave primary expression to its faith when

it celebrated the Eucharist. However, because of the Arian controversy in

the late 3rd and early 4th century, the Nicene Creed replaced the

Eucharistic Prayer as a means of handing on the faith of the church in the

Eucharistic Liturgy. It is suggested by our tradition that the Nicene Creed

be used on all major festivals and it or the Apostle’s Creed may be used on

Sundays. Most churches use the Nicene Creed on Sundays because it is

considered the great Creed of our faith and because it is more complete in

Trinitarian and Christological doctrine. Also, the fact that the Nicene

Creed is placed before the Apostle’s Creed (pages 188 - 190 in the BAS) as

an option in Sunday liturgy gives it priority.

|

↑

Back to top

The Sign of the Cross

Question:

Answer:

|

I see members of the Parish make the sign of the cross at different times in

the liturgy. Would you please tell me how the sign of the cross is

made? When are the appropriate times to make the sign of the cross on

oneself?

Customs, furnishings and symbols vary greatly;

it is no exaggeration to say that no two churches are exactly the same. In

some churches the celebrant at Eucharist wears traditional vestments:

chasuble, etc.; in others he wears an alb and large stole; in others a

surplice. Some churches use incense; some do not. Some altars have six

candles, some none. And so on. In some Anglican churches there are just a

few people that cross themselves; in other Anglican churches most people

cross themselves.

Customs, furnishings and symbols vary greatly;

it is no exaggeration to say that no two churches are exactly the same. In

some churches the celebrant at Eucharist wears traditional vestments:

chasuble, etc.; in others he wears an alb and large stole; in others a

surplice. Some churches use incense; some do not. Some altars have six

candles, some none. And so on. In some Anglican churches there are just a

few people that cross themselves; in other Anglican churches most people

cross themselves.

Perhaps this very diversity serves

to remind us how important ceremonial is -- and yet how secondary. Our

faith is in the living person of Jesus Christ, not in a set of things and

buildings. Jesus would still be Lord if every cathedral and parish church

were destroyed tomorrow. Yet all these external signs and symbols, properly

used, serve to increase our understanding of worship and, in the end, our

faith in him. Now to answer the two questions. I use the word ‘ceremonial’

to mean an action, something done by a worshiper during a service. The sign

of the cross is ceremonial. People who see the point of this ceremony are

sometimes shy of making it or uncertain how to do it. A safe way (however,

certainly not the only one) is to make the cross with one’s outstretched

hand, from the forehead, then touching the chest, then the shoulders, from

left to right. When you were baptized, you were given the sign of the cross

as a symbol of your faith, as the badge, the distinguishing mark of a

Christian. It was made upon your forehead. Now you make it for yourself.

When?

During worship, the sign of the

cross is by custom made at certain times. At the Eucharist these are as

follows:

-

when the priest says, “the grace

of our Lord Jesus Christ” etc. at the beginning of the service.

-

if the priest says, “in the name

of the Father” etc. before and/or after the sermon.

-

at the absolution when the priest

makes the sign of the cross over the congregation after the general

confession.

-

at the blessing at the end when he

also makes the sign over the people.

When the Gospel is announced, we

sign (with the thumb) forehead, lips, and breast, to show that we will take

the words to our mind, speak the words with our lips, and keep the words in

our hearts.

At Morning Prayer and Evensong the

sign of the cross is used as follows: on our lips with the thumb at the

words “O Lord open our lips”; in the usual way at “O God make speed to save

us”; at the beginning of the gospel canticles -- the Benedictus, the

Magnificat, Nunc Dimittis -- and at the end if the Grace is said.

It is worth mentioning that you will

from time to time no doubt be making the sign of the cross at other points

in the service, for example, at the end of the prayer “may the souls of the

faithful...” or “rest eternal grant unto them, O Lord, and let light

perpetual shine upon them”, at the end of the creed, or just before

receiving Holy Communion. This is because not so very long ago it was the

rule to make the sign of the cross much more frequently during the Eucharist

than it is now. Many people have kept to these habits and are not to be

criticized for so doing. |

The Cross as 'Sign' - The symbol of the Cross is

common to Christians of all traditions, and has been since the beginning of

Christian history. It is to be seen in art, in and on our Churches, and as

ornaments on our bodies. All of this is appropriate for Christians,

because the sign of the Cross constantly reminds us of what Christ did for us

all.

When we make the sign of the Cross, we are reminding ourselves of this. We

are also reminding ourselves that what Christ did on the Cross 'He did for me',

personally!

In making the sign of the Cross, we 'glory in the Cross of Christ' (Gal 6:14) ,

and we 'take up our Cross'. When we 'take up our Cross' we must be

prepared to say to God 'not what I will, but your will be done'. 'Not I,

but thou!'

The Cross as 'Prayer' - Very often when we make

the sign of the Cross, we do it to accompany another prayer. For example,

we make the sign of the Cross when we say the words "In the name of the Rather

... etc." In this case, the 3 points of the Cross may remind us of the

Trinity. Making the sign of the Cross is also a prayer itself: a prayer

without words.

It is fitting that when we come together in worship, we should worship with all

our being. We are to worship with our minds, our souls and also our

bodies, for our bodies are the "Temple of the Holy Spirit". Making the

sign of the Cross is nothing less than worshipping with our bodies, for what is

more fitting for the body than movement and gesture?

When we use words to pray, we are using only one form of language. The

body has its own language also, in which making the sign of the Cross is an

eloquent expression. One small gesture can speak volumes of words.

↑ Back to top

The Peace

|

Question: |

What is the purpose of the Peace

during the Eucharist? There’s lots of talking and visiting during the Peace

and this distracts from the service. Often it takes me a long time to get

my mind back into worshiping following the Peace because of this talking

between Parishioners. Would you please address this concern?

|

|

Answer: |

When the celebrant says, “The Peace

of the Lord be always with you”, we respond, “and also with you”. In the

early church each person turned to his neighbor and kissed him on the

cheek. This ceremony is enacted today by a handclasp. This is to show the

unity of the Body of Christ. Since the times of Saint Paul, the unity of

the worshipers has been considered the very essence of the service itself

(see 1 Cor 16:20, 2 Cor 13:12, 1 Peter 5:14 and Eph 4:3-4).

When the celebrant says, “The Peace

of the Lord be always with you”, we respond, “and also with you”. In the

early church each person turned to his neighbor and kissed him on the

cheek. This ceremony is enacted today by a handclasp. This is to show the

unity of the Body of Christ. Since the times of Saint Paul, the unity of

the worshipers has been considered the very essence of the service itself

(see 1 Cor 16:20, 2 Cor 13:12, 1 Peter 5:14 and Eph 4:3-4).

It’s important to note that the

peace comes after the confession and the absolution and before the prayer of

consecration and the receiving of communion. This is intentional! We must

be at peace with our God and with our neighbor before receiving the body of

Christ.

The peace is not the time to talk

about events of the past week nor our plans for the coming week. So the

peace (in the early church it was the known as the kiss of peace, also pax)

is the mutual greeting of the faithful as a sign of our love and unity.

Let’s enjoy it but let’s not get carried away by unnecessary talking. Let’s

be sensitive to maintaining the reverence of our worship during the peace.

|

↑ Back to top

The Holy

Days of Easter

PALM SUNDAY

and HOSANNA |

Question: What is the significance of Palm Sunday? And

what does Hosanna mean?

Answer: Palm Sunday is the 6th Sunday in Lent (the

Sunday before Easter) which commemorates the entry of our Lord into

Jerusalem, when people strewed the way with palm branches and cried

"Hosanna". It is an old custom on this festival to decorate the church

with palms, to carry them in procession, and to distribute blessed palms to

the congregation.

Hosanna is the Greek form of the Hebrew petition 'save we beseech Thee', a

song of praise to God.

|

|

HOLY WEEK |

The rites of Holy Week are ancient and by nature different from the

liturgical celebrations of the rest of the Church Year. They are meant

to be different in order to focus the attention of the people on the

mysteries being celebrated in this sacred time.

Therefore, it is important that the priest and all who assist in the Holy

Week rites be well prepared and familiar with what is happening. You

cannot over-plan for Holy Week. The extra time spent in preparation

and the extra attention given to details will contribute substantially to a

liturgical flow that will enable the people to participate fully in these

rites and will also avoid confusion.

|

|

TENEBRAE |

The name Tenebrae (the Latin word for 'darkness' or 'shadows') has for

centuries been applied to the ancient monastic night and early morning

services (Matins and Lauds) of the last 3 days of Holy Week, which in

medieval times came to be celebrated on the preceding evenings.

Apart from the chant of the Lamentations (in which each verse if introduced

by a letter of the Hebrew alphabet), the most conspicuous feature of the

service is the gradual extinguishing of candles and other lights in the

church until only a single candle, considered a symbol of our Lord, remains.

Toward the end of the service this candle is hidden, typifying the apparent

victory of the forces of evil. At the very end, a loud noise is made,

symbolizing the earthquake at the time of the resurrection (Matthew 28:2),

the hidden candle is restored to its place, and by its light all depart in

silence.

|

|

MAUNDY THURSDAY |

The liturgy of this evening should convey the strength of solemnity and

restraint so that the actions may speak for themselves. For indeed, it

is the beginning of the sacred 3 days of the celebration of the Passion and

Death of our Lord Jesus Christ. It initiates a time of watching,

waiting and contemplating, as we enter into the commemoration of the mystery

of our redemption. The gift of love in the Sacrament of Christ's Body

and Blood is the focus; the demonstration of self-giving in the washing of

feet is a fitting symbol; the watch through the night and the continuation

of this liturgy in that of Good Friday is the timelessness of silence, the

silence of God. On this night we celebrate the Great Thanksgiving with

the powerful knowledge that:

When the hour had come for

him to be glorified by you, his heavenly Father, having loved his own who

were in the world, he loved them to the end; at supper with them he took

bread...After supper he took the cup of wine...Father, we now celebrate

this memorial of our redemption (BCP,374).

|

|

THE WATCH |

Technically, a vigil is any period of watchfulness or wakefulness

that is kept through the night. It was quite common for the Early

Church to have nocturnal services of prayer, often ending with the

Eucharist. For example, the main celebration of Easter, the Paschal

Vigil Service, was observed during the night of Holy Saturday/Easter Sunday.

Traditionally, after the Mass (and Evensong) of Maundy Thursday, it is

appropriate that a Watch be kept throughout the night before the Reserved

Sacrament at the altar of repose. (Thus the term "The Watch" to

symbolize first the account of the Agony in the Garden, Mt. 26:36-46, then

Judas' betrayal, followed by Peter's denial). After the Maundy

Thursday Eucharist, the Reserved Sacrament shall be removed from the aumbry

and placed upon the altar until the completion of Compline. Following

Compline, the Blessed Sacrament shall then be taken from the altar and

placed at the back of the Church for the continuation of the Watch.

The Watch can be a very meaningful devotion. We pray that it will be

for many of you.

|

|

GOOD FRIDAY |

The Solemn Liturgy of the Passion and Death of Our Lord Jesus Christ should

be celebrated in the afternoon or early evening hours. It is a

continuation of the Maundy Thursday Liturgy and begins in silence as the

night before ended in silence. In order that the solemnity of this day be maintained, careful planning and

preparation are necessary. Nothing should detract from the total

participation of all the people in the celebration of this liturgy.

Before the liturgy begins, the place of Reservation should be darkened so

that all attention may be focused on the action in the sanctuary. A

single lamp should be kept burning, signifying the sacramental presence, but

all other candles should be extinguished.

The main altar is bare, without linens or frontals. There are no

candles. If possible, all crosses should be removed until the 3rd part

of the liturgy.

|

|

THE GREAT VIGIL OF EASTER |

The Great Vigil of Easter is the culmination of the sacred celebration of

Holy Week and the beginning of the celebration of the Lord's Resurrection.

It is the climax of the Christian Year and unfolds in Scripture, psalm,

Sacrament and liturgy the story of redemption. It begins in darkness

and proceeds to a joyous burst of light. It begins in silence and

proceeds to the glorious proclamation of the Paschal Alleluia.

It is the Christian Passover, for it celebrates the passing from death to

life, from sin to grace. The story of the Exodus is central to the

Liturgy of the Word; Baptism is the means of the full realization of

redemption; Holy Communion is the promise of the glory that shall be ours

with our Risen Lord.

This liturgy moves with austere solemnity from one part to the next, as we

watch and wait for the Lord's Resurrection. It is not to be rushed

through, for time is suspended as we recount the story of creation,

celebrate the glory of the New Creation in the waters of Baptism, and

profess our faith in the perfection of all creation in the fullness of time,

in the glory of God.

Of all the celebrations of the Church Year, the Great Vigil of Easter is

pre-eminent, for it alone vividly and dramatically portrays all that was,

that is, and that ever shall be in the drama of our redemption:

Christ yesterday and today, the Beginning and the End, the Alpha and

Omega. His are the times and ages and to him be glory and dominion

through all the ages of eternity. Amen.

|

↑ Back to top

Upcoming Events

|

Notices of Interest

|

Sunday School

|

Teen Scene

|

Outreach

Rector's Greeting

|

Our

Clergy

|

Lay Leaders

|

Our

History

|

Our Core Beliefs

Devotional

|

Newsletter

|

Photo Gallery

|

Annual General Meeting Reports

Testimonials

|

News &

Blogs |

Anglican Traditions

|

Links

|

|